Tec de Monterrey, Mexico.

Tec de Monterrey, Mexico.

When I studied there in 2002, I was stunned by the state-of-the-art facilities and the pristine campus which featured colourful peacocks.This will be the first of three entries on the subject of debt-for-education swaps in Latin America.

For the past five months I have been working at the Organization of Iberoamerican States, developing a booklet that explains:

a) The importance of investing more in Latin America’s education systems,

b) The burden of the debt, particularly on education spending, and

c) Debt-for-education swaps as an innovative solution to the debt and education crises.

This entry will focus on the first argument: The importance of investing more in Latin America’s education systems.

Latin America faces two enormous obstacles to development: extreme inequality and enormous debt. Indeed, Latin America is the world’s most unequal and most indebted region.

These impediments reinforce one another: as governments dish out more dollars to service their debts, they have less money to spend on social services, such as education and health.

In over half of Latin America’s countries, more money is spent paying back the debt than on education.

The region is caught in a development trap. Debt-for-education swaps attempt to tackle both of these issues at the same time. Before analyzing the debt problem, it is necessary to address the following question:

How important is investing in education to the development of Latin America?

First and foremost, education is a fundamental human right. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory.”

From an economic development perspective, there is a consensus that investment in efficient, effective and equitable education leads to greater employment, higher wages, higher productivity, and greater economic growth for both individuals and society.

From a social development perspective, education serves a broad range of functions, from saving lives (ie early detection of disease and illness) to empowering vulnerable populations, such as women, the poor, and indigenous populations to overcome discrimination.

From a political development perspective, investment in education means having a stronger foundation for democracy. Anyone who has been frustrated by how a populace can elect an dumb person to power, will usually find a difference among the education levels of those who voted for each of the candidates.

In sum, education is probably the single most important investment governments, societies, families and individuals can make.

For anyone who has been to Latin America, the unequal access to quality education is shocking.

For instance, Tec de Monterrey in Mexico, with its luxurious commodities (all students have laptops and access to wireless internet anywhere on its picture-perfect campus), is light years ahead of the countless shantytown schools that lack books, electricity and are rat infested.

The rich have unbounded privileges to progress, while the poor remain trapped in a vicious cycle of exclusion, illiteracy, hunger, disease, and insecurity.

The region invests at best less than half as much as do developed countries (comparing Chile with Spain) and at worst one thirtieth as much (comparing El Salvador with the US).

As well as raising funding levels, many difficult policies need to be implemented. For instance, the well respected public universities are generally tuition-free. While the intention behind this policy is a noble one, the reality is that these universities are often filled with privileged students who attended superior private and public schools that better prepare them for the competitive entrance exams. Since it doesn’t cost these students anything to study, many have little incentive to complete their degrees on time, and many drag a four year diploma into seven years of wasted time and resources.

Latin American societies are essentially subsidizing richer students to study at the highest level, while many of the poor who never make it that far, remain discriminated against.

The question of discrimination cannot be overlooked.

Nowadays, when a government institutes discriminatory policies against a race, it is openly and justifiably called racism. However, when exclusion is colour blind and not declared as official policy, few people dare utter the word classism (fittingly, my spell checker tells me that the word doesn’t even exist).

I am drawing this parallel because I recently read Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, A Long Walk To Freedom. Given the project I am working on, several paragraphs jumped out at me:

Mandela eloquently states: “Education is the great engine of personal development. It is through education that the daughter of a peasant can become a doctor, that the son of a mineworker can become the head of the mine, that a child of farmworkers can become the president of a great nation. It is what we make out of what we have, not what we are given, that separates one person from another.”

Mandela goes on to describe the apartheid education policies that helped institutionalize racism. Prior to apartheid, the United Party provided curricula for both whites and blacks that were essentially the same and all students were instilled with what were considered ‘liberal’ values at the time. Although Mandela studied under extreme racism, he recognizes that “we were limited by lesser facilities but not by what we could read or think or dream.”

Once the apartheid Nationalists came to power, “the disparities in funding tell a story of racist education. The government spent about six times as much per white student as per African student…The Afrikaner has always been unenthusiastic about education for Africans. To him it was simply a waste, for the African was inherently ignorant and lazy and no amount of education could remedy that.” (Long Walk to Freedom, 166).

In Latin America, the poor (whether they are black, indigenous, mestizos or white) face institutionalized classism. The far inferior level of education they receive is proof of this discrimination. While racism is undeniably a serious problem, it is essential to address all forms of discrimination in an integrated manner. Only through quality, equitable education can this be achieved.

Certainly, improving education is not the cure-all for the region. But it is probably the single most important step today’s leaders can take.

Almost two years ago Latin America’s Ministers of Education declared a regional movement in favour of education. However, if these countries continue to spend more on servicing its debt than on education, such a promise will be hard to keep.

This past year Argentina took an innovative approach to breaking out of this trap. The government announced that it will be conducting a debt-for-education swap with Spain. Money freed up by cancelled debt will be injected into the nation’s poorest neighbourhoods. About $78 million will be converted into 200,000 scholarships for children who have been excluded from the education system.

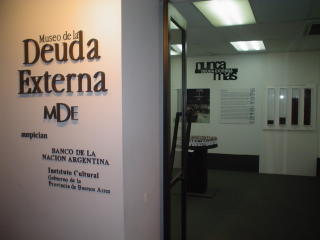

World's first debt museum?! This past week I finally made the trip to Argentina's Foreign Debt Museum at the University of Buenos Aires' School of Economics.

World's first debt museum?! This past week I finally made the trip to Argentina's Foreign Debt Museum at the University of Buenos Aires' School of Economics.