Debt-for-Education Swaps: Part I

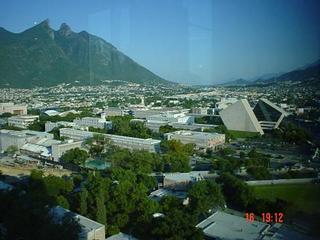

Tec de Monterrey, Mexico.

Tec de Monterrey, Mexico.When I studied there in 2002, I was stunned by the state-of-the-art facilities and the pristine campus which featured colourful peacocks.

This will be the first of three entries on the subject of debt-for-education swaps in

For the past five months I have been working at the Organization of Iberoamerican States, developing a booklet that explains:

a) The importance of investing more in

b) The burden of the debt, particularly on education spending, and

c) Debt-for-education swaps as an innovative solution to the debt and education crises.

This entry will focus on the first argument: The importance of investing more in

These impediments reinforce one another: as governments dish out more dollars to service their debts, they have less money to spend on social services, such as education and health.

In over half of

The region is caught in a development trap. Debt-for-education swaps attempt to tackle both of these issues at the same time. Before analyzing the debt problem, it is necessary to address the following question:

How important is investing in education to the development of

First and foremost, education is a fundamental human right. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory.”

From an economic development perspective, there is a consensus that investment in efficient, effective and equitable education leads to greater employment, higher wages, higher productivity, and greater economic growth for both individuals and society.

From a social development perspective, education serves a broad range of functions, from saving lives (ie early detection of disease and illness) to empowering vulnerable populations, such as women, the poor, and indigenous populations to overcome discrimination.

From a political development perspective, investment in education means having a stronger foundation for democracy. Anyone who has been frustrated by how a populace can elect an dumb person to power, will usually find a difference among the education levels of those who voted for each of the candidates.

In sum, education is probably the single most important investment governments, societies, families and individuals can make.

For anyone who has been to

For instance, Tec de Monterrey in Mexico, with its luxurious commodities (all students have laptops and access to wireless internet anywhere on its picture-perfect campus), is light years ahead of the countless shantytown schools that lack books, electricity and are rat infested.

The rich have unbounded privileges to progress, while the poor remain trapped in a vicious cycle of exclusion, illiteracy, hunger, disease, and insecurity.

The region invests at best less than half as much as do developed countries (comparing

As well as raising funding levels, many difficult policies need to be implemented. For instance, the well respected public universities are generally tuition-free. While the intention behind this policy is a noble one, the reality is that these universities are often filled with privileged students who attended superior private and public schools that better prepare them for the competitive entrance exams. Since it doesn’t cost these students anything to study, many have little incentive to complete their degrees on time, and many drag a four year diploma into seven years of wasted time and resources.

Latin American societies are essentially subsidizing richer students to study at the highest level, while many of the poor who never make it that far, remain discriminated against.

The question of discrimination cannot be overlooked.

Nowadays, when a government institutes discriminatory policies against a race, it is openly and justifiably called racism. However, when exclusion is colour blind and not declared as official policy, few people dare utter the word classism (fittingly, my spell checker tells me that the word doesn’t even exist).

I am drawing this parallel because I recently read Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, A Long Walk To Freedom. Given the project I am working on, several paragraphs jumped out at me:

Mandela eloquently states: “Education is the great engine of personal development. It is through education that the daughter of a peasant can become a doctor, that the son of a mineworker can become the head of the mine, that a child of farmworkers can become the president of a great nation. It is what we make out of what we have, not what we are given, that separates one person from another.”

Mandela goes on to describe the apartheid education policies that helped institutionalize racism. Prior to apartheid, the United Party provided curricula for both whites and blacks that were essentially the same and all students were instilled with what were considered ‘liberal’ values at the time. Although Mandela studied under extreme racism, he recognizes that “we were limited by lesser facilities but not by what we could read or think or dream.”

Once the apartheid Nationalists came to power, “the disparities in funding tell a story of racist education. The government spent about six times as much per white student as per African student…The Afrikaner has always been unenthusiastic about education for Africans. To him it was simply a waste, for the African was inherently ignorant and lazy and no amount of education could remedy that.” (Long Walk to Freedom, 166).

In

Certainly, improving education is not the cure-all for the region. But it is probably the single most important step today’s leaders can take.

Almost two years ago

This past year

8 Comments:

Excellent, well-written post. One thing that I have found interesting is the middle classes (in countries that actually have a middle class) end up becoming college educated but they are not able to get good jobs. For example, I have middle class friends in Chile who have attended their countries top universities (albiet spent many year completing their degrees as you indicated) and who have found that they want to come to the US because they cannot find good employment in Chile. How can you motivate someone to go to school or university when they don't have any guarentee that their country can provide them with stable employment that can make them upwardly mobile?

Diego,

Excellent post, as usual. I agree with you that education is a fundamental human right and all governments have an obligation to provide their citizenry with quality education.

I liked the way that you wrote about education from three different perspectives (economic, social, and political), and I agree with the points you made. I only have one more thing to add: education is beneficial because children in school do not work as child laborers. While I do not think Latin America is as affected by child labor as India, child labor still exists in places like Brazil, and this is yet one more reason to invest in education. I am an admirer of Brazil's bolsa escola program (founded by the Cristovam Buarque, guest at the Alliance for the New Humanity!), which pays families who send their children to school.

You are right that the contrast in Mexico is incredible. Do you know that Mexico has such a teacher shortage that in rural classrooms in Tamaulipas (and other states), children do not even have human teachers? Instead, they have televisions with VCRs (known as "tele-secundarias") that are supposed to serve as education.

In India (like Latin America), the best universities are generally public (state funded). And just like in Latin America, wealthier students have access to private tutors and private tutors. In fact, India is probably even more imbalanced than Latin America for linguistic reasons: the majority of wealthy Indians speak English as a first language or virtually as a first language. In contrast, poor children speak their native language at home and usually struggle with English. Since English is the language of higher education in India, the Anglophone elite advantage is multiplied. I touched upon this phenomenon in my most recent post.

In India (since the 1950s), the government has had an affirmative action program for poor people and scheduled caste people. While this has not remedied Indian poverty (and has been much criticized), it has given some poor people and some lower-caste people a chance.

Diego, a question: besides Brazil, do you know of any Latin American countries that have affirmative action-style programs either based on race or income level?

A sidenote: one of the problems in implementing a racial AA program in Latin America is that race is quite fluid in Latin America. For example, in Brazil I was called white, black, mulatto, moreno, indio, indiano, and pardo! My race changed depending on who I was talking to. Unlike the United States, where races are clearly defined (see the comments section of this article), Latin America generally has had more fluid race definitions. But I am digressing…

Another sidenote: one way in which India has tried to combat the discrepancies in privilege has been though NGOs like Akanksha. Akanksha, for example, aims to send slum children to college, and therefore immerses the children in English (in addition to teaching values, math, and self-esteem empowerment). I think that NGOs can play a powerful role in leveling the playing field, but sadly, in my experience, many Latin American NGOs are ineffective.

On a different note: Diego, what role do you think culture has to play in education? Let me explain: in the United States, I have found that some groups (be it geographic, ethnic, religious, etc.) value education more than others. If Latin American governments invest more in education, how do you convince people to value education? How do you convince parents to urge their children to study, study, study?

Last thing: Christian's comment was very relevant. Even if people are educated, good jobs are very scarce in Latin America. In Mexico, for example, one cannot even start a small business anymore, since American corporations like Wal-Mart (with their massive economies of scale) dictate the terms of business. I should also state that a huge number of "Mexican" companies (registered in Mexico) are actually American-owned since the company is run by American capital and the profits flow north. I know Mexicans with masters' degrees and doctorates who cannot get decent jobs. How do you address Christian’s question?

I think university systems are in need of serious reform. Even though many of the public universities in Bolivia are "autonomous", they are rife with politics.

I do not completely understand the system, but it really encourages the participation of people who aren't that interested in studying. Sometimes you catch the news and see an interview with "student leader" and he is some 40 something guy talking about campaign platforms.

My comparision always goes back to my experiences studying in the U.S. Bolivian professors rarely participate in research, when in the U.S. tenure and promotion are often associated with their research output.

Don't get me started on private universities as they are often pay-for-diploma factories.

I do think that public universities should remain free for everyone regardless of economic class. Although special assistance should go to top students from rural areas and poor neighborhoods to help pay for housing or other costs. Also, there should be a limit on how long a student can take to complete a degree, which should help reduce the number of career students. Yes, there are some special cases where it takes someone longer.

All in all, education system in Bolivia from elementary school on up rarely encourages critical reasoning and only reinforces the idea that the professor (or any other leader in authority) holds all of the answers and that students should be honored to soak up any information given to them.

Christian:

The ‘brain drain’ you point out is important. It is very concerning that some of Latin America's brightest are leaving to the North in search of employment and higher wages.

While I am no expert on the issue of education and employability, I think the problem you raise has some deep roots that can only be fully solved in the long-term.

Structural adjustment in Latin America has been extremely painful, particularly for people our age and the generation to follow.

I say this because in most countries, low, single-digit unemployment figures from the 1970s have steadily risen. In some countries, the figure has grown to the 20% range in the past few years. New jobs are scarce, and youth unemployment is staggering.

Given the sweeping changes undertaken during the 1980s and 90s (widespread privatization, market deregulation, etc.) it is evident that future solutions require equally comprehensive policies.

Creating better quality education is insufficient on its own – especially since its dividends are not fully realized in the short and medium-term.

The issue of extreme inequality needs to be dealt with head-on. The region urgently needs stronger, progressive tax systems. Corruption at all state levels can no longer be given the impunity that it has enjoyed in the past. A culture of patronage and clientelism needs to be replaced by one of transparency and accountability.

I don’t think that there is a government in power that has the mandate to carry out these tough policies. Latin American societies remain quite polarized.

All of this being said, there are some immediate changes that can be made to the university system. For instance, as you probably know, there are too many people enrolled in law and social science degrees. The job market simply doesn’t offer enough job opportunities for these people. Meanwhile, there is a growing demand for people with technical and scientific backgrounds. In Argentina, some of these positions are not being filled. Universities must adapt to this reality.

So to answer you question directly: unless the above changes begin to sweep the continent (in much the same way the neoliberal structural adjustment policies did) I don’t think it will be easy to motivate young people to go to school or university (unless you offer financial incentives to do so, something I discuss below).

Vikrum:

I am glad you added a point that I forgot to make; mandatory education helps keeps children out of labour and sexual exploitation. While most benefits of education are observed in the medium to long-term, the point you bring up has to be one of the most salient benefits of providing universal, quality education.

You asked: besides Brazil, do you know of any Latin American countries that have affirmative action-style programs either based on race or income level?

Good question. Unfortunately, I do not know of any cases. If I come across any in my research, I will let you know. And you are quite right that racial labels are quite difficult to use in the region.

What role do you think culture has to play in education?

I agree with your view that some demographic groups place more emphasis on education than others. It is easy to stereotype: for instance, some groups value education because it has paid off for them in the past (ie Jews who came from Europe), or because they come from hard working, austere cultures (ie mainland Chinese).

Beyond these particular generalizations, it is important to draw some conclusions void of race, ethnicity, nationality etc. For instance, a growing global culture of consumerism is having an important effect on how education is being valued. Rampant consumerism in developing, very inegalitarian societies is particularly damaging.

I believe that education is essential for both instrumental and intrinsic reasons; as a means and as an end. I think it is important to maintain a balance between the two. Yet most people simply view education as a means to getting a job and making more money.

So to address your question: If Latin American governments invest more in education, how do you convince people to value education?

Like I said above, education should be valued as a means and as an end. For instance, education should be about instilling terminal values (equality, non-discrimination, solidarity etc.) while also providing instrumental ones (employable knowledge and skills).

An education system that is out of touch with societal norms and employment trends will likely produce a generation of apathetic, unethical, and out-of-work youths.

As I mentioned above, the solution is not a simple one. I believe that broad reforms have to be made. I would like to see them done in the most democratic way possible. I would love to see task forces that genuinely ask youth, parents, teachers, community leaders, private sector leaders what their priorities are for the education sector.

How do you convince parents to urge their children to study, study, study?

Most Latin American leaders recognize that their number one priority for their education systems is achieving 100% primary enrolment rates.

Argentina used to be at a 100%, but in the past few years around 500,000 children from its poorest regions were excluded. A program funded by the IDB, as well as the debt-for-development swap with Spain, will help integrate these children by providing their families with scholarship money as an incentive to send their kids to school.

Obviously, this is just a start. This doesn’t ensure that these children will study hard, or that they will receive quality education. But considering the alternatives (begging, soliciting, digging through garbage, selling their bodies etc), it’s a critical step in the right direction.

Eduardo:

Thanks for sharing your experiences with the Bolivian university system. I agree with your idea of “there should be a limit on how long a student can take to complete a degree.” I also agree that critical thinking is scarcely encouraged.

However, I also think that making sure upper class kids pay some kind tuition will ensure that there are funds for providing scholarships for lower class kids. I think the Canadian university system provides a reasonable balance between government subsidies and personal contributions (the average Canadian student pays between $3000-$6000 per year).

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Hi, Diego. Great Blog. I am an American-Argentinean CPA doing voluntary work @ Fundacion SES, sponsored by UBA Ciencias Economicas, regarding debt swapp x education, specially cash flow from and to Argentina, tools to consolidate information with focus in international Cooperation. any info or data about it will be greatly appreciated.Should you be interesed I will also share my findings with you.Sincerely.Luis

Post a Comment

<< Home