Debt-for-Education Swaps: Part II

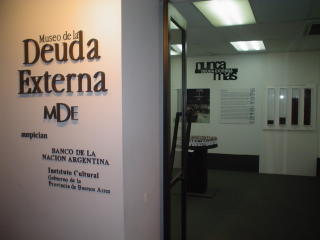

World's first debt museum?! This past week I finally made the trip to Argentina's Foreign Debt Museum at the University of Buenos Aires' School of Economics.

World's first debt museum?! This past week I finally made the trip to Argentina's Foreign Debt Museum at the University of Buenos Aires' School of Economics.The blue light box displays the faces of the Ministers of Economy who presided over the debt explosion during the dictatorship (1976-83). The wall is covered in press clippings reporting political developments.

A corner of the museum is dedicated to ex-President Carlos Menem's golden age of indebtedness, privatizations, pegging the peso to the dollar, and his surgically enhanced smile.

Never again. We are convinced that this tragedy cannot be allowed to repeat itself. We have to generate a collective consciousness so that we can be aware of the economic decisions taken by our leaders. Indebtedness has not only resulted in sending great quantities of resources overseas (resources which could have been used for health, education, help for the poorest etc.), but it has also been the main weapon used by concentrated capital to carry out neoliberal reforms which have destroyed the country’s productive structure.

Brochure from the

‘Never again’ (Nunca más) is an internationally used slogan to condemn genocide and crimes against humanity. In

By invoking nunca más, the creators of the

Indeed, the debt incurred by the military regime is a criminal act on its own. When the dictatorship took power in 1976, the country’s debt stood at $8,3 billion. When the regime fell in 1983, they had indebted the country to a whopping $45,7 billion. Not surprisingly, most documents and records of the debt had been destroyed.

The museum uses World Bank data to show where these loans ended up: 44% of the funds were used to finance capital flight, 33% went to paying interest to foreign banks, and 23% were used to import arms and non-identified goods. It is also estimated that the military nationalized $15 billion private sector debt; that is, bailouts for businesses friendly to the dictatorship.

There is a growing international consensus that debts incurred by illegitimate governments, like

However, given

The central point I am trying to make is this: economic policies are not carried out in a vacuum by Finance Ministers or World Bank economists. It is essential to understand that the major social, economic and political changes initiated in

The explosion of Latin American debt is a case in point. The debt crisis is much more than a problem of irresponsible lending and borrowing. Debt initially skyrocketed under the auspices of anti-democratic, corrupt, and criminal practices. Not surprisingly, the crisis has been accompanied by several policies which have failed to create sustainable growth, employment, greater equality or reduce poverty for almost three decades.

In 2004,

As I mentioned in my previous post, debt servicing exceeds education spending in over half of the region’s countries. This trend must be reversed.

Yet I am not sure if blanket debt forgiveness is part of the solution.

While I view the recent G8 deal to forgive the debt of 18 of the world’s most poorest countries as a promising step forward, there are reasons to be cautious. Oddly enough,

In my next post, I will expand upon the problems with blanket debt-forgiveness, and how debt-for-education swaps offer an alternative.

5 Comments:

Hey Robert,

Glad you enjoyed the article. I am always interested in a expat's perspective on living in BA. Even if you aren't going to use the section you wrote on the economy, I would love to read it.

Diego

buen trabajo

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Post a Comment

<< Home