Diego Armando Maradona

If

For those not too familiar with ‘El Diego’, here’s a brief recap (otherwise skip to the next section):

Diego is born in a

At 21 he plays in his first World Cup; he is ejected for a violent retaliation. The team makes an early exit. He lands a $8 million contract with

At 25 he travels to his second World Cup. Single handedly carries

At 29 he travels to his third World Cup. Single handedly carries an even weaker national side to the final. He plays with ankles swollen twice their size. I saw them in a magazine. This time they lose in the final. Diego cries. The nation cries. He is battered yet doesn’t quit.

At 33 he travels to a record tying fourth World Cup. I go to see him score his last goal in

In 1997 he retires from football. His career with cocaine carries on. In 2000, he suffers from an overdose induced heart attack. He turns to Fidel Castro’s health care system for help. He becomes quite obese during his therapy. Gastric bypass surgery in

***********

Now that I have summarized Diego’s career, let me get to the point I was making.

In 1986 Maradona single handedly won the World Cup.

In 1986 Maradona single handedly won the World Cup.

Top: Maradona garnered the utmost attention of the synchronized Belgian defenders.

Bottom: the karate kicking Koreans figured out the best way to stop Maradona.

Argentina

Maradona is captured using what he calls the “Hand of God” to punch in the first goal against the English. His second goal, a stunning individual performance which is often recognized as the best goal of all time, sealed the victory. This past week Diego recognized that he punched the ball into the net and doesn’t regret it. He then referred to the English capturing Las Malvinas (

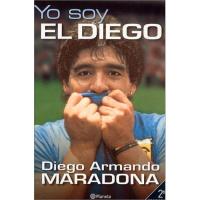

The title of his autobiography, “I Am The Diego”, alludes to the unparalleled fame he has acquired. Maradona is so famous that he can refer to himself in the third person (Shucks! That means that my name is already taken). I found a great quote from a former teammate, and soccer great, Jorge Valdano: “Poor Diego. For so many years we have repeatedly told him, ‘You're a god’, ‘You're a star’ ... we forgot to tell him the most important thing: ‘You're a man’.”

Maradona (center) in his hometown of Villa Fiorita, a slum outside

Argentina

Maradona with his 1996 Ferrari F355 Spider. He eventually had to sell it. It is now be auctioned on the internet. Go here to bid on it. The highest bid so far is $670,550.

In the 1994 World Cup my dad and I drove down to

Argentina

After almost 20 years of cocaine use, and several overdoses, Maradona had a near fatal heart attack. Enough was enough. He sought medical attention in Fidel Castro’s medical paradise. According to this Mexican newspaper, cocaine, sex and videotapes were readily available at the clinic.

Argentina

During his rehab the 1.68 metre (5’6”) Maradona inflated to 121 Kgs (266 pounds)!

A post-stomach stapling Maradona on his new talk show, “La noche

Argentina

Top: Maradona with new friend Hugo Chavez. Maradona later said: “The truth is I like women, but I fell in love with him (Chavez).”

Middle: Maradona showing his long time friend Castro, a tattoo of Fidel’s face on his leg.

Bottom: Maradona showing off his famous Che tattoo.

Maradona also spent time some time in Libya with Qadaffi and trained his son, the captain of the national soccer team, with his good friend Ben Johnson (yes, the scandal ridden, ex-fastest man in the world). A close source tells me Ben and Diego indulged in copious amounts of cocaine, while frequently complaining about the lack of prostitutes and alcohol in the Libya.

Top: Brazilian “Super Size Me” gag on Maradona’s cocaine diet.

Middle: A piggish Maradona using a straw to snort a cocaine laced field.

Bottom: Instead of playing soccer, “The Maradona’s Team” inhales the white powdered lines on the field.

During his farewell match at Boca Junior’s stadium, Maradona was thanked for everything he has done for the country. When he recently recovered from his addiction, he was given the Vice President title at the club. I am sometimes taken back by how much his ass is kissed, but then I remember that I am in the land of fútbol, and El Diego es Dios.

Argentina

Lionel Messi, 18, led

Finally, in

Che’s and El Diego’s mugs side-by-side. The caption reads: Fútbol Revolución.