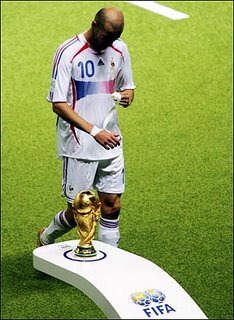

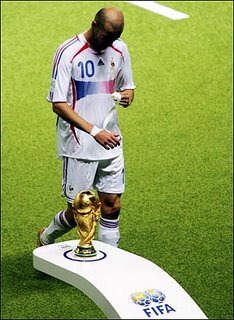

As the dust settles, it seems Zidane’s flagrant foul has captured more headlines than the Italian championship team. This bizarre distraction seems to be linked to the sensation that the World Cup is increasingly anti-climactic and unjust.

The head-butt heard round the world upstaged the most popular sporting final because millions of die hard fans have been let down by some or all of the following: controversial rules, inconsistent officiating, creativity crushing defensive strategies, frustrating under-achieving, and rampant unsportsmanlike behaviour.

Zizou’s split-second decision to spearhead Materazzi has managed to symbolize that which is the good, the bad and, the ugly of this World Cup. Given how the good has been overshadowed by the bad (and the ugly), I’ll save the best for last.

The Bad.

Anti-climax. Too much hype, too little football, and too popular a head-butt.

Like most fanatics, I twiddle my thumbs anxiously for the four years between each tournament to pass. In Canada, I’ve always been disappointed by the poor media coverage and general apathy towards the tournament (beyond certain immigrant groups).

After watching my first World Cup in Argentina, I have discovered what is to suffer from a severe mundial overdose, and consequent hangover.

The media coverage is insane. One TV channel, TyC Sports, offered 24-hour month-long broadcasting. This was complemented by at least four or five other channels doing their best to compete with the TyC stranglehold.

Given the endless air time dedicated to the tournament, every imaginable, trivial news item was reported. From cultural tours of the town hosting the national team’s pre-tournament training grounds, to what the players ate at each meal, what they did in their spare time, which family members paid them visits, what time they went to bed, and when Carlos Tevez had diarrhea - all 38 million Argentines were injected senselessly with information.

During these 30 days, the entire country, myself included, was in a state of intoxicated patriotic hypnosis. I tried to sober up and ask myself: “Is this drunken passion good for Argentina?” Part of the answer was a clear, yes. It brings people from all walks of life together, unites them in the name of a fantastic sport, and fills them with pride and hope.

On the other hand, people invest so much emotionally and physically, that they detach themselves from everything else that matters and should matter to them. Drug addiction has a similar effect. The submission is so deep, that Argentines are destined to suffer immensely (something which has been happening consistently for the past 20 years). Anything short of a World Cup championship is by definition anti-climactic and unjust.

Stepping outside of the Argentine do-or-die mind frame, any football fan will tell you that it is not just the sore losers who are suffering.

The sport is suffering. Beckham's pretty boy circus act epitomizes this decadence.

The highly touted tournament has been failing to deliver the best football for quite some time now. As such, each tournament leaves its die hard fans wanting a lot more, or having to settle for a spectacular head-butt.

The Ugly.

Football injustice. This collective let-down I am trying to describe is underpinned by a sense of injustice which football purists have been complaining about for some time now.

This unfairness is a combination of some or all of the following: controversial rules, inconsistent officiating, overpowering defensive strategies, frustrating under-achieving, and rampant unsportsmanlike behaviour.

Unfortunately my humble call for reform needs to be undertaken by one of the slowest evolving, highly secretive, all-powerful corporations of the world: FIFA. Instead of improving the tournament, it appears that the organizers are more preoccupied with finding ways to spend the €1.9bn earned in marketing revenue, the €700m raised from tournament sponsorship, not to mention the ticket sales.

Here are my proposed reforms:

1. Rule changes

Teams generally spend two years trying to qualify for an event which lasts a mere month. This is disproportionate. Anti-climax is almost an inherent outcome of the World Cup.

To ensure a more competitive and balanced tournament, I would double the amount of games and extend the duration of the tournament to two months. The format remains the same. As done in the qualifiers and other popular tournaments (such as the Champions League), each match-up would be played out in two games instead of one.

Having teams play each other twice would minimize the chances of a team going on a hot streak and making the World Cup by fluke (as they will have to play 14 games instead of 7 to win the tournament).

This would also would increase rivalry and excitement. Perhaps this would even encourage less experienced, but very skilled squads, particularly those from Africa to overcome first game jitters against more experienced teams and have a chance to redeem themselves after a poor start.

As it is, losing two games and having to say goodbye after such a long journey is too harsh.

Secondly, penalty kicks have to be scrapped. It’s unfair to decide a game with a one-on-one roll-of-a-die situation in a sport which prides itself on teamwork, tactics and creativity.

One solution would be to play endlessly until the sudden death golden goal is scored. The substitution of all 11 players would have to be allowed as players begin to drop like flies after two hours of play. This wouldn’t entail any serious changes, as there already are 23 players on each roster (some of whom never get playing time as it is).

Thirdly, the introduction of video replay. While I am not convinced of the need for video replay during matches (as it would bring time stoppage to a free flowing game), I am all for the retroactive penalization of dirty fouls and unsportsmanlike conduct (particularly diving). It would be great to see Cristiano Ronaldo get publicly fined and/or booked for his Greg Louganis impersonations. And if it can be proven that Materazzi taunted Zidane with racist insults than he should be punished as well.

Finally, having to sit a player out a game for having accumulated two yellows in separate matches is ridiculous in such a short tournament. Especially when yellows are handed out for dumb offences such as taking of your jersey to celebrate a goal. The number should be upped to three or four yellows.

2. Consistent officiating

I generally come to the defence of referees. It’s is so easy to blame everything on them, from Italy’s victory over Australia to Global Warming.

The World Cup is supposed to feature the best officials in the world, yet several matches, as in past tournaments, were decided by critical errors. The referees sent off a record number of players, yet glaring mistakes were rampant, and divers constantly went unnoticed. I wont list the controversies, but luckily someone over at Wikipedia has already.

With such a large pitch and 22 players to follow, one referee is simply not enough. A second referee needs to be added to ensure that they are close enough to the tackles to decipher legitimate fouls from dives.

3. Defense first strategies

World Cup 2006 was the second lowest scoring tournament in history (only after the even more abysmal 1990 championship). This is nothing new, as teams have been far more concerned with preventing goals than scoring them for quite some time.

This is a calculated strategy by most coaches. Some, such as Italy and France, have adopted a very conservative 4-4-1-1 arrangement, enabling their teams to defend with 8 players (leaving only one creative midfielder behind a lone striker).

Unfortunately, offensive minded teams, such as Brazil, did not do well in Germany. Their 4-2-2-2 formation is one of a kind. Defending with only a maximum of 6 players, Brazil took a calculated risk in putting their faith in the unparalleled talent of their stars. A risk most fans of the game want Brazil to take. Unfortunately, the Brazilian players that we all know did not show up to this tournament (something I address in the next point).

Then there is the schizophrenic case of Argentina. A creative, offensive minded team which gains a lead but then ends up emulating defensive European squads. Teams like Brazil and Argentina defend best when they maintain ball possession and continue attacking. Unfortunately, in tight games coach Pekerman was reluctant to play the team’s most feared offensive weapons. Against Germany he paid dearly for sitting on a 1-0 lead, instead of opting for Messi and going for the kill.

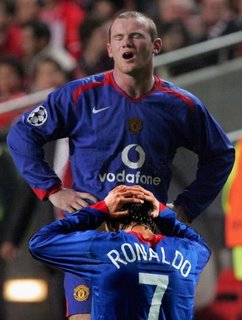

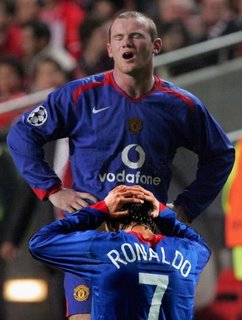

4. Underachieving stars. The likes of Rooney and Cristiano Ronaldo have disappointed in more ways than one.

What happened to the stars? The world’s best player, Ronaldinho, disappeared. Robinho, Adriano, Kaka and company barely showed up. Ronaldo, despite all of the fat and criticism, was Brazil’s biggest threat.

Rooney, disappointing. Lampard, nothing. Owen, injured. Ballack, the best we saw of him was a dive. Messi, more time on the bench than on the pitch.. Schevhenko, surrounded by the most mediocre of team mates. Totti, nice haircut.

Figo, Cristiano and Deco had their moments, but were distracted by their other hobbies: acting, diving and whining.

Are these disappointing performances due to these things I’ve been ranting about? Is too much pressure created a hyped-up, unjustly short tournament? Is relaxed refereeing failing to protect the stars? Or is strict officiating encouraging the stars to dive? Does anyone have a solution to overcome these stifling defensive strategies?

Since the stars couldn’t shine by heading the ball past defenders, they might as well end up learning how to head-butt defenders.

5. Unsportsmanlike behaviour.

I’ve already touched upon this already. Diving needs to be disciplined retroactively and severely. Ironically, FIFA could learn how to handle the problem by following in the footsteps of the violent National Hockey League. Last year the NHL began publicizing, fining and eventually suspending players for diving.

This being said, FIFA should be very careful in identifying what is acceptable and what is unacceptable when it comes to simulation. This article does a good job describing which simulations should be considered cheating and which ones are actually necessary in order to protect the star players (although I disagree with the author’s point regarding the penalty awarded at the end of the Italy-Australia game).

The Good.

Tevez and Ribery, unlike pretty boys Beckham and Ronaldo, exceeded expectations. Clearly, it's what's on the inside that counts.

Despite my endless ramblings on the bad and the ugly, a few good things can be salvaged from the mediocre tournament.

Best team. Given how tight and competitive each game was, particularly in the second round, there was no clear-cut ‘best’ team of the tournament.

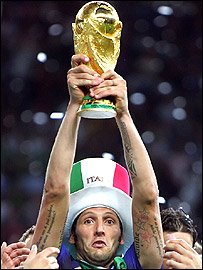

Italy did what it had to do to win and that was defend for around 89 minutes and attack for the rest. They relied on the best defense in the world tostifle France’s creative players. Unfortunately they won in the most dubious of circumstances: penalty kicks, following the sending off of the World Cup’s star player.

Italy deserves more credit for how they beat Germany. It was probably the match of the tournament. When penalties were imminent Lippi made some bold changes, bringing on three forwards to win the game in regulation time. Something Argentina should have attempted instead of defending like a frightened turtle.

Best offensive display. Argentina put on a goal scoring clinic against Serbia and Montenegro, a team that during qualifications only conceded one goal. The 25-touches before Cambiasso’s finish and Tevez’s solo charge ranked as the second and third best goals of the tournament.

Best goal of the tournament. Maxi’s game-winning outside-the-area off-the-chest into-the-top-corner volley was almost as surprising and exciting as Zidane’s head-butt.

The best player. Tough call. Zidane’s performance against Brazil was jaw dropping. A Frenchman playing like a Brazilian against Brazil. Unbelievable. However, he was non-existent the first two games, got himself suspended for the third game, and we all know what he did with only 10 ten minutes left in the tournament.

Cannavaro was far more consistent than ZZ, but less spectacular since he is a defender. It would have been nice to see a defender get the prize for once. But then again, people are entertained by goals and not by tackles.

In a tournament in which taunts, dives, tackles, saves, penalties, bookings, and slurs ruled supreme it is no surprise that Zidane was sent off for a gross violation and yet still received the best player of the tournament.

Given all of this, Zizou’s head-butt, stands out as an almost dignified rebellion against those things which attempted to destroy the World Cup. When he apologized to all the kids of the world for his retaliation, he should have also said sorry for the sad state of soccer.